R.I.P. My Chicago Books

By Donald G. Evans

If you go by what didn’t get ruined, it’s a lot of good news. All of the Sara Paretsky books, just about: fine. The signed Chicago Literary Hall of Fame induction ceremony and Fuller Award booklets: safe. Signed copies of Bellows’s Augie March and Gwendolyn Brooks’s’ In the Mecca: untouched. A lot of it, really.

But if you go by what did get ruined, it’s simply heartbreaking.

Flood overwhelmed the basement at which I store my entire Chicago book and memorabilia collection. A backed-up sewer pipe. Eight to ten inches of water. Foul water.

Wading through the drenched, compromised boxes, I stumble across items I’d forgotten, or at least not thought about in years.

Richard Christiansen’s beautiful coffee table book, A Theater of Our Own: A History and a Memoir of 1,001 Nights in Chicago, rested on the bottom shelf of one of those basement bookcases. When I pulled it off the shelf, the miracle I’d quietly entertained didn’t happen. Drenched through and through. I bought that copy at the Goodman Theatre, already signed by the author. I was there for a matinee performance of Hughie and Krapp’s Last Tape starring Brian Dennehy, who’d written the forward to the book. I was there with my old friend Jay Raemont and his mom, whom I adored. The two were in Chicago from McHenry. I can’t remember now what day it was—I’d check the ticket stub from that day, but it was inside the book and is also ruined. Maybe a Thursday. This had to be a half-dozen years after the book came out in 2004. Jay and his mom wanted to pop off to eat, but they were good sports about me hanging around the lobby a bit. Eventually, Brian Dennehy, a big man and bigger than life, strolled out of the side door, where I made my introduction. Brian Dennehy took my pen and signed the book right near his byline at the front; then he signed the Stagebill and the ticket stub. The night after I got home from the theatre I began looking at the photos, and then read Brian Dennehy’s remarks. I skipped around the pages, reading some of Richard Christiansen’s wonderful narratives. I remember being inspired to seek out theatres to which I’d never been, find out about plays I missed. I remember thinking, “Man, I have to appreciate what we have here more than I’ve appreciated it. I have to TAKE ADVANTAGE.”

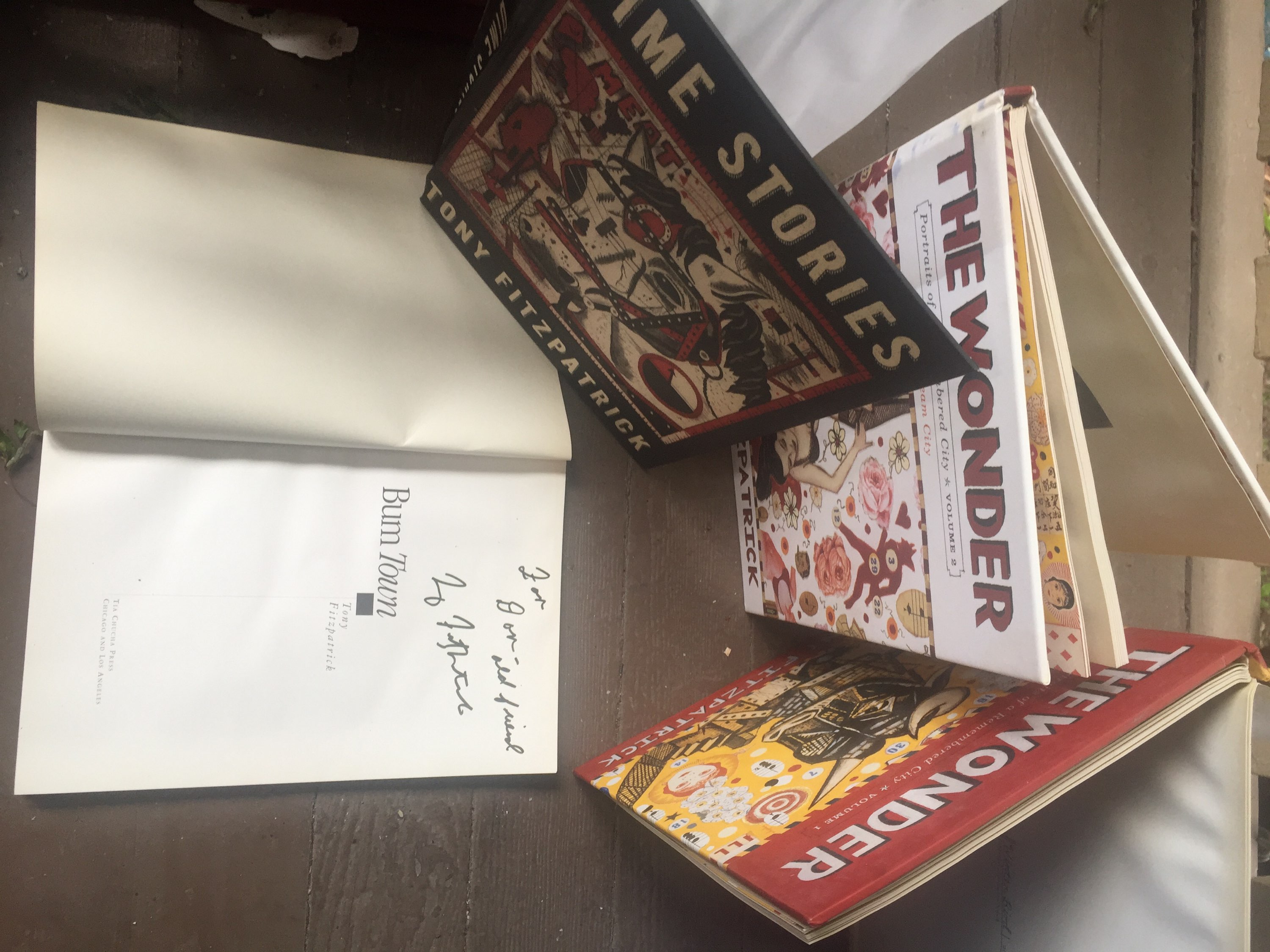

All of Tony Fitzpatrick’s books were in a cardboard box marked, “F,” and from a distance I could see the water mark reached almost to the top. I started pulling out the books. I first met Tony at a party he threw on the occasion of his friend Jonathan Demme being in town. This was at his parents’ house in Villa Park at a time when I was working as a  reporter/editor at the local newspaper there. Years later, I tracked Tony down and asked him to blurb my first novel. He asked me to bring down the galleys to his studio and when I did I also brought a copy of Bum Town for him to sign. Bum Town is one of my favorite Chicago poetry books, a riveting and touching story grounded in our city. Shades of Algren in there, but also Farrell and Dybek. “To my old friend,” he wrote. Later, I popped in on a Max and Gaby’s Alphabet signing at Quimby’s, where Tony held court for several hours, telling great, funny stories as people filtered in and out, but mostly pulled up chairs. Then there was a launch party at Fitzgerald’s in Berwyn for his Dime Stories, and a Lit Fest panel with Rick Kogan and Bill Hillmann, where I picked up another title. The collection took years to complete. Now completely wiped out.

reporter/editor at the local newspaper there. Years later, I tracked Tony down and asked him to blurb my first novel. He asked me to bring down the galleys to his studio and when I did I also brought a copy of Bum Town for him to sign. Bum Town is one of my favorite Chicago poetry books, a riveting and touching story grounded in our city. Shades of Algren in there, but also Farrell and Dybek. “To my old friend,” he wrote. Later, I popped in on a Max and Gaby’s Alphabet signing at Quimby’s, where Tony held court for several hours, telling great, funny stories as people filtered in and out, but mostly pulled up chairs. Then there was a launch party at Fitzgerald’s in Berwyn for his Dime Stories, and a Lit Fest panel with Rick Kogan and Bill Hillmann, where I picked up another title. The collection took years to complete. Now completely wiped out.

Bayo Ojikutu’s Free Burning and 47th Street Black: gone. I’d just heard Bayo Ojikutu speak as part of a panel discussion on novel and short story writing—this was, I think, the DePaul Summer Writing Conference at the DePaul Center on South State Street. I’d been impressed at Bayo’s patience and intelligence, the way he talked about his writing process. He’d also read a short passage, a piercing excerpt with attention to language and characters, and especially setting. Before he got halfway through his reading, I knew I had to know the whole story. When the discussion ended, I bought both Bayo’s books—this was 2009, according to the soggy inscriptions. Bayo was stationed behind a table with the other authors off to his right. A woman, then a man, went up to his table and got their books signed, then it was just me. I introduced myself while Bayo signed the books. There was nobody behind me in line, so we kept chatting. Mostly about Chicago books we loved and all the friends we had in common. I left there feeling I knew Bayo just a little; by the time I’d finished his two novels I felt like I knew him a lot. Those books represented to me not only great literature, which they are, but the beginning of a treasured friendship.

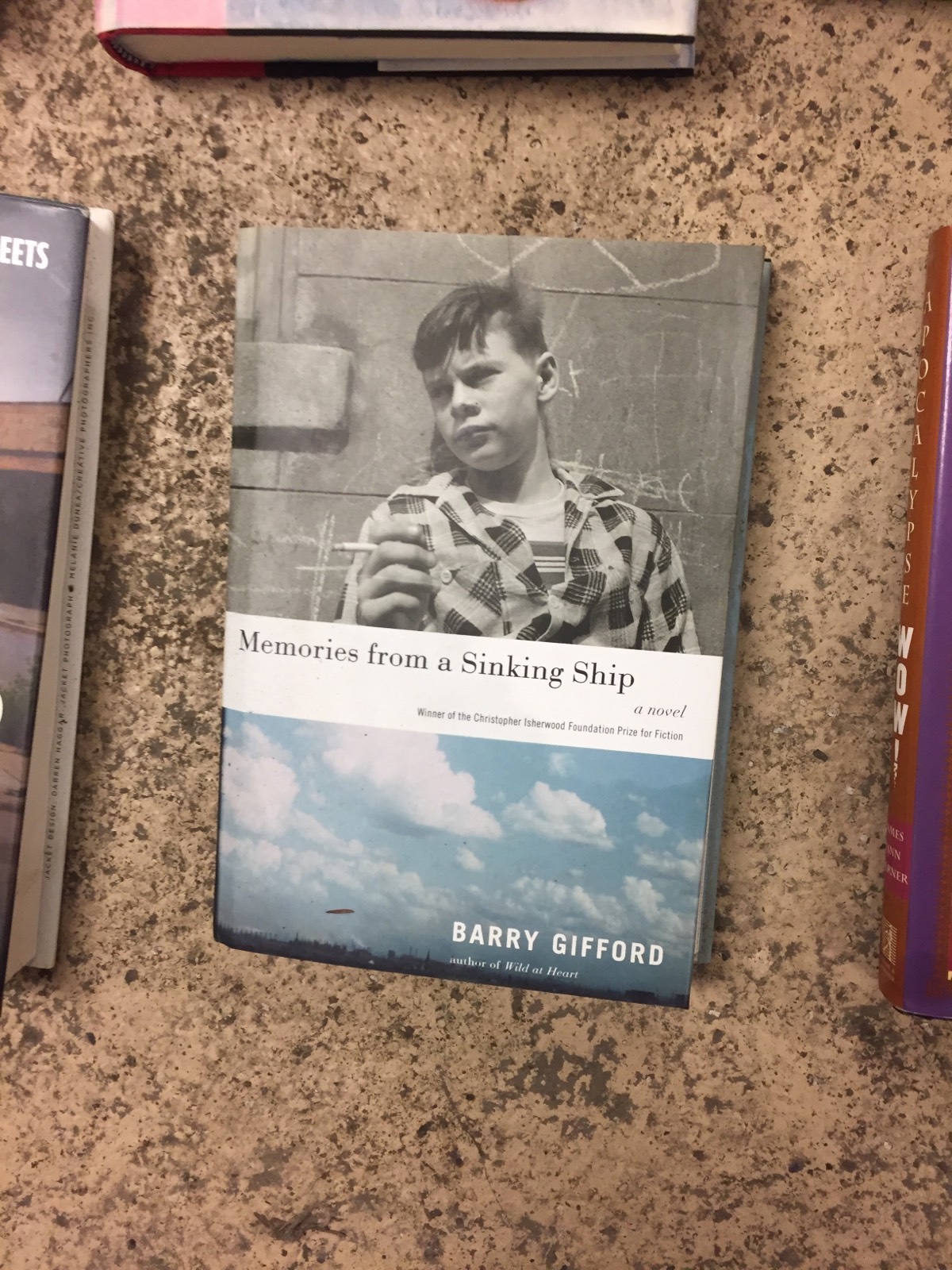

I hardly knew Barry Gifford’s work before he was to appear at Columbia College’s Story Week Festival in 2014. I’d been meaning for a while to read more, especially his Roy  Stories, which I’d heard beautifully captured Chicago at a certain time. I knew I was going to the festival and would get the opportunity to buy a few books there, but I wanted what would not be available outside the auditorium. I ran around to Myopic and Unabridged and other used stores and found a whole stack of quality first editions. I started reading the books and knew after a short time that Gifford belonged in the same conversation as some of the great Chicago story tellers whose invented worlds explode the idea of neighborhood. Listening to Gifford talk was mesmerizing and I felt lucky that no more time had passed before I’d made his work part of my life. There at the Columbia building on Wabash, the author patiently signed my books: one, two, three, all the way to 17. I’d read through about three-quarters of those books when that bastard sewer pipe took them all. Every one of them.

Stories, which I’d heard beautifully captured Chicago at a certain time. I knew I was going to the festival and would get the opportunity to buy a few books there, but I wanted what would not be available outside the auditorium. I ran around to Myopic and Unabridged and other used stores and found a whole stack of quality first editions. I started reading the books and knew after a short time that Gifford belonged in the same conversation as some of the great Chicago story tellers whose invented worlds explode the idea of neighborhood. Listening to Gifford talk was mesmerizing and I felt lucky that no more time had passed before I’d made his work part of my life. There at the Columbia building on Wabash, the author patiently signed my books: one, two, three, all the way to 17. I’d read through about three-quarters of those books when that bastard sewer pipe took them all. Every one of them.

Jim Garner’s Rex Koko trilogy took an unfortunate bath, as well. Double Indignity, Honk, Honk My Darling, and The Wet Nose of Danger. It was 2008, and as unlikely as it sounds now, Chicago and really a lot of the country were SURE that the Cubs were about to end their drought. It was the centennial of the team’s last World Series championship in 1908. I started a reading series called Lovable Losers—we met once a month at El Jardin on Clark Street, just south of Wrigley Field. Maybe that was a Monday night when we’d go there. The idea was we’d read poems and stories, sing songs, tell jokes, and generally bring a literary sensibility to our journey, which I knew would end either in elation or more of the same. Either way, I’d already entertained the idea that this series would be the springboard for an anthology, and I had the shape of that anthology already in my head. But we needed really good writers and performers to participate in this thing, otherwise it would just be us eating a lot of tacos and taking up Janie Alvarez’s back room. I don’t remember how I tracked down James Finn Garner—maybe he already had his own website then—but I do remember how thrilled I was that he said, “Sure, I’ll come read.” I’d already been a fan of Jim’s Politically Correct series and owned several of the books. Between when Jim agreed to be there and the night of the reading, I visited four or five of my favorite used bookstores—I found several more of Jim’s books, and when I arrived at the restaurant that night I had a shopping bag half filled with them. You’ve seen crazy book collectors like myself at events—you look at us and you think, “I don’t want to get behind THAT GUY in line!” I was a little sheepish—I mean, Jim walked in with a few printed pages scribbled with some last-minute notes, not expecting this to be a book signing, because it wasn’t. And here I was, loaded for bear. I got those books all signed, and later, as Jim started writing his series of clown noir novels featuring Rex Koko, I went out to amazingly fun launch events at places like the Book Cellar (where there was a whole carnival fire show in the square, not to mention Jim in clown outfit wearing a sandwich board) to get new titles one by one. As Jim became a friend, I cherished those books even more. Not all of those books are gone, but there is now for sure holes in my collection.

It was through Jim I met Jonathan Eig. Sometimes, with my Chicago collection, it’s hard to categorize. Mostly, I assemble my books by author, but with Get Capone it also belonged with my sub-set of Chicago gangster titles. Jon Kobler’s The Life and World of Al Capone, which I found at an Open Books sale at their Pilsen store. Fred D. Pasley’s 1930 biography Al Capone, unearthed in the Chicago section of the Newberry library sale. And Kenneth Allsop’s The Bootleggers: The Story of Chicago’s Prohibition Era, which I hadn’t gotten around to reading. Those were all on that overwhelmed bottom bookcase shelf, along with Bryan Alaspa’s Silas Jayne and Joe Kraus’s The Kosher Capones: History of Chicago’s Jewish Gangsters. But no matter that I separated Jon’s books—that collection as well as a box that included his Lou Gehrig and Muhammad Ali biographies both got hit.

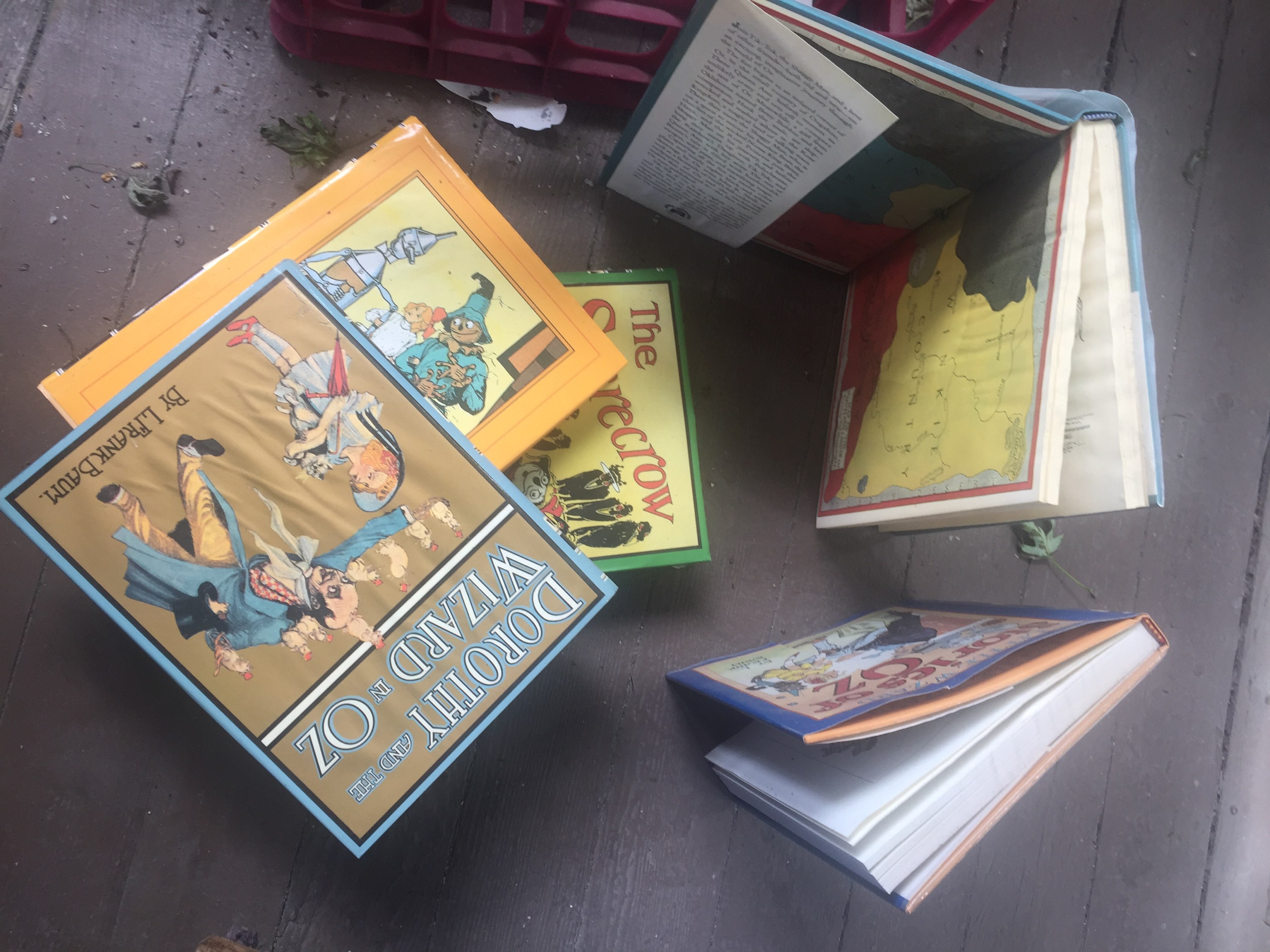

I’d gotten in the habit of checking out vintage copies of the Wizard of Oz series, at rare book shops and under glass cases at antique stores. Unaffordable—that was the constant conclusion. I wanted those and thought I’d just have to do without, but then I stumbled across an illustrated fine set edition published by Wonder Books. Stunning  books, lavishly illustrated. On this, I splurged, knowing I’d own every novel plus all the stories. I read them one by one to my son Dusty, some of them twice, and we’d pause to admire the artwork. Of all the enormously important memories I have of Dusty at that tender age, reading to him still ranks as my favorite. Then I dusted the books off when my nephew Evan was around seven—I lugged the whole box from Chicago to New York and back. Evan took to them, too, and I remember teaching him how to handle the books. There were these genius built-in silk bookmarkers and we ALWAYS used those rather than setting the book open and risking a cracked spine. Almost half of those books were ruined in the flood, and having an incomplete set of this type feels like having nothing at all.

books, lavishly illustrated. On this, I splurged, knowing I’d own every novel plus all the stories. I read them one by one to my son Dusty, some of them twice, and we’d pause to admire the artwork. Of all the enormously important memories I have of Dusty at that tender age, reading to him still ranks as my favorite. Then I dusted the books off when my nephew Evan was around seven—I lugged the whole box from Chicago to New York and back. Evan took to them, too, and I remember teaching him how to handle the books. There were these genius built-in silk bookmarkers and we ALWAYS used those rather than setting the book open and risking a cracked spine. Almost half of those books were ruined in the flood, and having an incomplete set of this type feels like having nothing at all.

I first became aware of Reg Gibbons’s work at Printers Row Lit Fest, probably when it was still being called something else. This had to be ten years ago. He read at the Arts & Poetry Stage from his collection Slow Trains Overhead: Chicago Poems and Stories. I’d already purchased a copy of the book at the seller’s table, and followed along as Reg read. I was struck, both in the writing and reading, at the author’s enormous command of the language, the unusual care he took in every poetic construction, and the nuance of his choices. Here was somebody who was clearly a master creator but more than that somebody who’d turned his life over to the world of language. That was the only Reg Gibbons book I had then, and he signed it. Eventually, Reg would participate in dozens of Chicago Literary Hall of Fame affairs, at which I had him sign a half-dozen of his poetry collections, plus his fiction titles. I had just coincidentally made a mental note to bring the books home (they always go back and forth) to start rereading in advance of CLHOF’s ceremony to honor his lifetime achievements. I wanted to do a complete inventory as part of the work I’ll do to assemble the commemorative program for his award night. Now, there is nothing to inventory.

I was working, tentatively, on a partnership with 826Chicago, an exhibit that fit the spy theme they then used for their bookstore. Hilary Hodge, then head of its board, encouraged me to come out to their space on Milwaukee Avenue—there was a get together with Dave Eggers, the brilliant author and founder of the 826 programs here and elsewhere. I always buy at least one book, often several, at an author appearance or signing—I feel it’s proper form and only fair, to the book sellers, authors, and venue. But I cannot afford to build a library with a preponderance of books for which I pay retail price. Plus, sellers tend to bring out mostly paperback copies of all but the latest title, and I want the hardcovers--first editions, when possible. So, I brought books, maybe a half-dozen, that I’d found at thrift shops or cheap online over the years. But 826 had a stunning array of Dave’s books for sale and each in itself was a work of art—beautiful bindings, lush illustrations, fine cloth covers. I bought a bunch, both because I wanted them and because this is how I like to spend my new book money—at a store, museum, or organization that I want to support anyway. Dave talked to me as he signed what by then had turned into a considerable pile of my books. I told him about the CLHOF and he said, “If you never need anything, get in touch.” He was due to come to Chicago to help us honor Luis Alberto Urrea before that event was postponed a month ago. I’d looked forward to seeing him again and getting him to sign the books I’d amassed since that night at 826. Sadly, my Dave Eggers collection has been reduced to a few titles.

I didn’t think I’d make it to The Hideout that night in 2018. I had another event and it was possible but not likely I’d be able to duck out in time. I wanted to hear the live podcast recording of Illinois Turns 200 and to say hello to Paul Durica, Natalie Moore, and Tom Dyja, among friends that would be featured on the show. I also knew Ann Durkin Keating would be there. I knew her as the co-editor of Encyclopedia of Chicago. It’s a doorstop of a book, but one that I’ve used more than most over the years. I wanted to get her and eventually James R. Grossman to sign, but given its size and that I probably wouldn’t even get there, I left it at home. Ann was so fascinating that the whole time I listened, standing in the back of that crowded bar, I thought, “Fuck! Should have brought the book.” Later, I found copies of her Rising Up From Indian Country and Chicagoland: City and Suburbs of the Railroad Age at The Dial Bookshop. Reading through her work, it was hard to believe it had taken me this long to get to it—such penetrating and thorough research, such elegant prose. I reviewed her latest book for Newcity—a book I adore--and had already staked out her appearance schedule to get my treasure trove of editions signed. Now, nothing’s left except for the latest—even Encyclopedia of Chicago had been moved to that evil basement.

would be there. I knew her as the co-editor of Encyclopedia of Chicago. It’s a doorstop of a book, but one that I’ve used more than most over the years. I wanted to get her and eventually James R. Grossman to sign, but given its size and that I probably wouldn’t even get there, I left it at home. Ann was so fascinating that the whole time I listened, standing in the back of that crowded bar, I thought, “Fuck! Should have brought the book.” Later, I found copies of her Rising Up From Indian Country and Chicagoland: City and Suburbs of the Railroad Age at The Dial Bookshop. Reading through her work, it was hard to believe it had taken me this long to get to it—such penetrating and thorough research, such elegant prose. I reviewed her latest book for Newcity—a book I adore--and had already staked out her appearance schedule to get my treasure trove of editions signed. Now, nothing’s left except for the latest—even Encyclopedia of Chicago had been moved to that evil basement.

I’ve known Angela Jackson quite a few years—ten, I’d say, or around there. She is one of our great Chicago writers, whose work simply sings. It has a certain charm, beauty and depth all rolled into one. Reading Angela Jackson is an adventure. Over the years, Angela has served on a Chicago Literary Hall of Fame selection committee, spoke at important occasions like the Gwendolyn Brooks statue dedication and the Fuller Award for Haki Madhubuti, and been honored for her lifetime achievement. She has sat in my living room, and me in hers. Every time, or nearly, I have books for her to sign; it’s how I’ve built up such an impressive collection of her published work. Somehow, Dark Legs and Silk Kisses got separated from the rest. No doubt, it was because I had pulled it out of its proper box to read and then returned it to some unlabeled bag or bin. I’ve been looking for that book for more than a year. It bothered me that it might be lost for good and that my Angela Jackson collection would be incomplete. I knew it had to be somewhere, but the exact location of that somewhere eluded me. I found it, mixed up in a box with some James McManus books I’d also recently re-read, as well as several of Haki’s books. Totally, completed wrecked. Lost, found, and lost again.

My great friend Robin Metz passed away in 2018, and among the relics I have of our friendship were his inscribed copy of Unbidden Angel and his signature on a lobby poster of The Day Carl Sandburg Died. The director Paul Bonesteel interviewed Robin, as well as Penny Nivens, for that documentary. All three had signed the poster, which for some reason I’d yet to get framed—probably waiting to collect signatures from some of the other subjects. I was in Galesburg for the premiere of the film—so, of course, was Robin, who’d been hunkered down at Knox College almost fifty years at that point. Penny was there, too. I can’t remember the first time Robin invited me to Galesburg, but over the years I went five or six times—to lead a panel discussion, or read a poem at the Sandburg statue dedication, to be a part of this or that workshop. Each of those trips was glorious—a couple days packed with Sandburg scholars and fans. During these times, I got to know a bunch of writers, like Penny (also now gone), as well as actors and so forth, some of whom later appeared at CLHOF events like our induction ceremonies. The Mayor of Galesburg and the President of Knox College even came out when we inducted Carl Sandburg. Having that poster was a way, every once in a while, to reminisce—but water plastered it to another poster and when I tried to separate the two the colors, images, and signatures peeled away, leaving me no choice but to toss what remained.

I could go on and on, but I won’t. I can’t. Not every book I own means something to me. There are a lot I haven’t read. There are some I honestly don’t like. There are duplicates, which I grab up at thrift stores in order to give to friends or put in Chicago Literary Hall of Fame auctions. But many of the destroyed items (in addition to books and posters and programs, there were LPS, such as Lorraine Hansberry reading A Raisin in the Sun, and 45s, like the theme song from the Hollywood production of A Man with the Golden Arm) ARE precious. WERE precious. I’ve often thought, “Stop, Don!” This hobby takes too much time. Way too much space. I didn’t need to own all these books—that’s what libraries are for. But this was MY library. I found comfort in knowing these things were there, and that one day, perhaps as part of the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame’s permanent home, others could enjoy all of this. Besides, these books remind me of places, people, and times in my life.

Some items might be replaced; others, never. For now, it’s best to think of what is still there—as I said, it’s a lot. There’s no profit in worrying over loss, but there is some comfort in mourning it.