By Donald G. Evans

By Donald G. Evans

Plumbers were out of work. Carpenters, too. Secretaries and seamstresses and waitresses. The Great Depression stripped so many of their livelihoods, for so long, that the country moved in a slow, grim line of hardship, some better off than others, but only a very few escaping the impact of the economic plunge.

Writers, too. Established writers and fledgling writers alike found nowhere to turn, the market for their skills as editors and researchers and copy writers, often employed in support of their true ambitions to create art that didn’t draw a paycheck, or only so in rare instances, dried up.

The government of the United States stepped up. As we contemplate now, during a time when controversy swirls about the amount of direct relief checks being issued to our country’s suffering unemployed, it is instructive to look back at this time. The plan then was simple: give resources to the needy in exchange for their hard work. The unemployed get paychecks and the country reaps the benefits of a talented mass of workers.

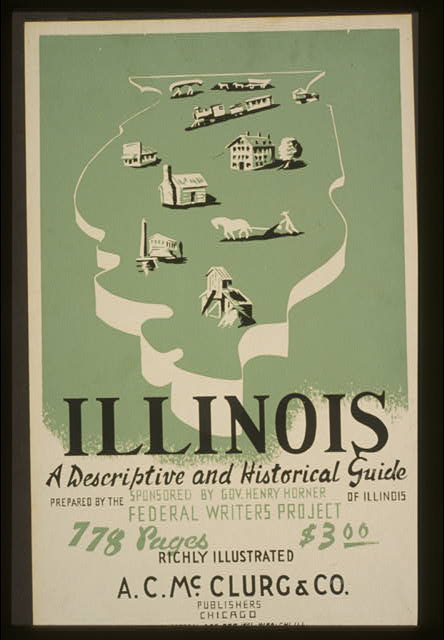

The Works Progress Administration, with nearly $5 billion in initial funding in 1935, built parks, schools, roads and post offices, all projects, for the most part, that received widespread public support. The Federal Writers’ Project, a department of the WPA, met with more resistance, critics charging, “we’re funding Communists,” “these are mediocre writers,” and so forth. That criticism (some of it valid) no doubt changed the shape of the FWP, but did not stop it from becoming an enormously important and effective endeavor. About 6,500 unemployed writers made a living wage of $20 per week working directly for the United States government. As was the plan, this program matched the skills of the idle with the needs of the country. It’s a testament to our national consciousness at that time that art was considered a need.

David A. Taylor, in his study, Soul of a People: The WPA Writers’ Project Uncovers Depression America, writes, “When Nelson Algren said that the Project gave hope to people who had lost it, he was not being melodramatic. The Writers’ Project set a trampoline under many thousands, writers and nonwriters, who would otherwise have hit the pavement.”

Chicago, perhaps more than any other city, prospered from this arrangement. Among the Chicago writers involved in the project were at least six future Chicago Literary Hall of Fame inductees: Algren, Saul Bellow, Studs Terkel, Margaret Walker, Fenton Johnson, and Richard Wright. Other important writers, including Arna Bontemps, Jack Conroy, Frank Yerby, Sam Ross, and Katherine Dunham, also participated in the project.

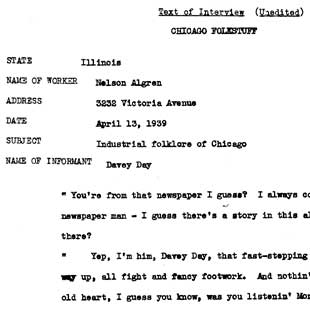

There were different assignments for writers, editors, and researchers, the most prominent being work on the state guide books, brilliant narratives that have been reprinted over the years and attained a collectible status. But the most fascinating department in which these authors gathered was Folklore. It was there, under the direction of WPA’s folklore editor Benjamin A. Botkin, that hundreds of life histories were recorded and written. Botkin worried about at the rise of fascism in Europe and the possible consequences of that trend at home. He hoped, in assembling diverse life histories, to encourage tolerance and understanding—the tenants of a democratic, pluralistic community.

Brian Dolinar, who edited The Negro in Illinois: The WPA Papers, argues that the most remarkable accomplishment of the project was the inclusion of so many black writers, which for the first time gave voice and perspective to everything from slave narratives to urban sociological studies.

Brian Dolinar, who edited The Negro in Illinois: The WPA Papers, argues that the most remarkable accomplishment of the project was the inclusion of so many black writers, which for the first time gave voice and perspective to everything from slave narratives to urban sociological studies.

Algren wrote a guide to Galena, and conducted many interviews, including one with a prostitute that made its way into his fiction, notably in A Walk on the Wild Side. Terkel wrote radio scripts on topics such as “Great Artists” and “Legends of Illinois,” later incorporating some of his interviews and subjects into his oral history projects and books. Wright, in the spare time afforded him through his employment, wrote a draft of Big Boy Leaves Home, later to become A Native Son. Ross conducted a series of interviews with jazz musicians, which he later repurposed in his fiction, including the novel Windy City.

Botkin regarded the life history narratives as "the stuff of literature" and he anticipated that Federal Writers would draw upon them as raw material. He wanted to move “the streets, the stockyards, and the hiring halls into literature."

Beginning Feb. 16 and running six sessions through March 23, I will be leading a seminar on the Chicago writers of the WPA. The seminar offers an overview of the Federal Writers’ Project with an emphasis on its Chicago writers. We’ll look at some of the work produced for the project and some that resulted from that experience. We’ll also examine some of the relationships that started or solidified during the FWP’s life, relationships that led to many collaborations and friendships, that paved the way for community writers groups, literary journals, anthologies, and dramatic productions. Finally, we’ll investigate government-funded programs today and examine the prospects for a revival of government-funded work for writers.

There are still some slots available. Sign up through the Newberry Library’s website if you want to participate in the six-week course.